Click here to listen to Inanna and Dumuzi: Her honey man (part 2 of 4) in the season 2 archives on buzzsprout

In this episode I tell the second part of Inanna’s story, the courtship and marriage between Inanna and her honey man, the shepherd Dumuzi. I’ve always delighted in the description of their courtship and the way it captures the excitement and hesitation that is part of falling in love and discovering the power of your sexuality.

At the same time, I bridled at the need for such a powerful goddess to marry and make her husband king. But is this merely a patriarchal degradation of a woman who rules heaven and earth? Or is their union, expressed in the language of a fertile and creative earth, a metaphor for the immanent divine? For the eternal spark in every life and material form that supports our existence?

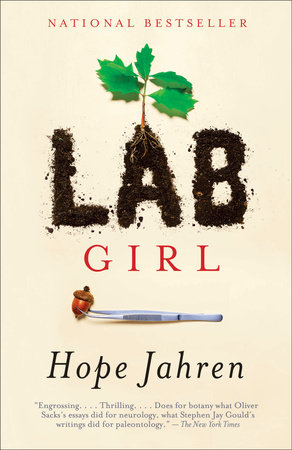

If so, is there a way for their coupling to translate into a lived experience for us today, distant as we are from the image of a holy couple who seed each other to sustain the earth? I turn to the opening pages of Lab Girl by geobiologist Hope Jahren to aid in this reflection.

Until next time, please take all precautions to protect your health and that of others. Every life is too valuable to lose.

Transcript of Inanna and Her Honey Man (part 2 of 4)

Hello, and welcome to Myth Matters, storytelling and conversation about mythology and why myth matters to your life today. I’m your host and personal mythologist Dr. Catherine Svehla. Wherever you may be in this wide, beautiful, crazy world of ours, you are part of this story circle.

Well, this is the second in a four part series on the Sumerian myth of Inanna, the goddess who was called Queen of Heaven and Earth. As I said in the last podcast, if I look at these times that we’re in, times of tumult, change, transformation–transformation for sure, from a mythological perspective, what I see is a quest for new metaphors. People talk about the fact that we’re in between stories, that we need a new story, meaning a new myth, and that’s true. And the route or the possibility begins in a metaphor, or an image, what Joseph Campbell called a “living symbol,” that can inspire and guide us in the creation of a new set of values and so then a new way of living.

I believe that this ancient story of the Sumerian goddess Inanna has a lot to offer us, and this quest must begin, like any quest, where we are, which means delving into our mythological inheritance. This is a very interesting story. It’s beautiful. It’s one of my favorites. And it comes from a time when the old world of the goddess and the new people who were coming in with patriarchy and monotheism, were mixing it up. In the first podcast, I told you the myths of Inanna that involved her tending the Huluppu tree, making her bed and her throne from it with the aid of the hero Gilgamesh, and then going to visit the God of waters and wisdom, Enki, and managing in a drunken encounter to come away with all of the mé, that is the powers and ordering principles of the civilization. So, Inanna has established the symbols of her two sources of power. And she’s visited Enki and acquired real power behind those symbols. And now what?

Well, the myth or hymn to Inanna that I want to share with you today is about the courtship of Inanna and Dumuzi. Inanna’s brother Utu, the sun god, comes to her and tells her that the flax is grown and ready to harvest. And the implication is, she should note this because she is in her fullness too. The flax is like the tree in the earlier podcast. a metaphor for Inanna. She is as Judy Grahn said, the mind in nature. She is life.

The Courtship of Inanna and Dumuzi

So, Utu goes to his younger sister and he says that the flax in its fullness is lovely, and that the grain is glistening in the furrow. And he offers to hoe it for her and bring it to her because she probably needs a piece of linen.

“Brother” says Inanna, “after you’ve brought me the flax, who will comb it for me?” “Sister” says Utu, “I will bring it combed.” “And Utu, after you’ve brought it to me combed, who will spin it for me?” “Inanna, I will bring it to you spun.” And then she asks, “Well, if it’s spun, then who’s going to braid it?” Utu says he’ll take care of that. “But then who’s going to warp it?” “I’ll take care of that for you, too.” “Who’s going to weave it for me? Who’s going to bleach it for me?” In this exchange, you get the sense that Inanna is excited about the possibilities but also hesitant to move on to the next phase of her life. And what is that phase? Well, Utu tells her when we have this all prepared, of course, we will make from this flax, a linen bridal sheet for you.

Hmm. “Okay” Inanna says to her brother, “after you’ve brought the bridal sheet to me, who will go to bed with me?” And he says, “Sister, your bridegroom will go to bed with you. And he will be your equal. He will also be fertile. He will also be divine. He will have his own powers. It’ll be a beautiful, beautiful thing.” He reassures her. And then Utu says, “In fact, your bridegroom, your husband, will be the shepherd Dumuzi.” Inanna says, “Oh, no, no brother, the man of my heart works the hoe. The man of my heart is the farmer. He is the one who grows the grain and brings it regularly to my store houses.”

“Sister,” Utu counsels, “marry the shepherd. Why are you unwilling? His cream is good, his milk is good. Everything that he touches shines brightly. And Inanna marry Dumuzi, as you are rich and beautiful, and so is he and what he will bring to you.” Inanna counters her brother and says “No, the shepherd, I won’t marry the shepherd. His wool is rough. I will marry the farmer, because the farmer grows the flax for my clothes and he grows the barley from my table.” Now Dumuzi appears and he says to Inanna, “Oh, why are you speaking about the farmer? I mean, whatever he can give you, I can give you the equivalent. I mean, if he gives you bread, I can give you cheese. And in fact, I have so much that whatever you don’t want, whatever is left over, I can give to the farmer What does he have Inanna, more than I do?”

“Well,” she said, “Shepherd you are only around and doing well because of my mother and my grandmother and my father and my brother. And they’re kind of pushing you forward here too, putting you in my face.” But Dumuyzi says “Now Inanna, don’t start a quarrel. My family is as good as your family. You know, my father is Enki. My mother is a goddess and my sister Geshtinanna, is as good as yours. So, we know this isn’t about family. Queen of the palace, let’s sit together and talk it over. You know that I am as good as Utu and you know that my family is as royal and as powerful and as divine as yours.”

The word they had spoken was a word of desire. From the start of a lovers quarrel came the lovers desire. Dumuzi the shepherd brought gifts of cream and milk to the royal house. He knocked on the door and called for Inanna to come and let him in. Inanna ran to her mother Ningal and asked her, “What shall I do?” “My child” said her mother, “there’s nothing to fear from this man who will be your husband. Get dressed to receive him and open the door.” Inanna bathed and anointed herself with scented oil. She put on her fine white robes and arranged her precious lapis bead necklace around her neck.

Dumuzi waited outside expectantly. At last Inanna opened the door. She shone as bright as the moon. Her light filled the house. Dumuzi looked at her joyously and pulled her close and kissed her. Inanna said “What I am about to tell you Dumuzi, must be woven into song and always remembered. My vulva is the Boat of Heaven, and eager as the new moon. But my land lies fallow. Who will plow my vulva? Who will plow my high field? Who will plow my wet ground?” “Great lady” said Dumuzi, “I will plow your vulva. I, Dumuzi the shepherd and king.” “Then do it man,” she replied. At the king’s lap stood the rising cedar. When this happened, the plants flourished. When this happened, the grain flourished. When this happened, the gardens flourished luxuriantly.

Inanna sang. she called Dumuzi the one her womb loves best, her apple tree, her impetuous caresser of the navel and the soft thighs. She called him her honey man, her honey man who came to her and made a honeyed moon. Dumuzi sang, saying that Inanna’s bounty was like a rich outpouring of plants, and grains and milk and sweet water. “Pour it out for me Inanna” he said, “pour out your abundance and I will drink all that you offer.” “My husband” Inanna said, “I will guard my sheepfold for you. I will watch over your house of life, the storehouse, the shining, quivering place which delights Sumer. The house which decides the fate of the land, the house which gives the breath of life to the people. I the queen of the palace, will watch over your house.”

Dumuzi took Inanna to his garden to see his orchard of apple trees. They walked among the trees together. And there they made their final pledge and they made love. “He met me” Inanna says, “he met me. My lord Dumuzi met me. He put his hand into my hand and he pressed his neck close against mine. Oh, the plants and the herbs in his field are ripe. Oh Dumuzi, your fullness is my delight.”

Having made love as innocent lovers, they now made their pledge as king and queen. Inanna called for the holy bed, for the holy bed of queenship, the bed of kingship, and the bridal sheet. She calls to Dumuzi, “The bed is ready. The bed is waiting.” Dumuzi came now as her husband and once again put his hand in her hand. Sweet is the sleep of hand to hand and sweeter still the sleep of heart to heart.

Now Inanna, lover, wife and Queen made Dumuzi the shepherd, her lover and husband, the king of Sumer. She gave him a crown and throne and scepter. “I will lead you in battle and protect you” she told him. “On the campaign, I am your inspiration. When you sit on the lapis lazuli throne and cover your head with the holy crown, I will be by your side and I will bind you myself with the garments of kingship. You are the chosen one shepherd, and in all ways you are fit. May your heart enjoy long days because I, Inanna, hold you dear. I will inspire and provide for you as wife and Inanna Queen of Heaven and Earth.”

Ninshubur, Inanna’s sukkal (that is her minister, ally and friend) came to the couple and seconded everything that Inanna had pledged. “Under Dumuzi’s reign” she says, “let there be vegetation, and under his reign let there be rich grain. In the marsh field, may the fish and birds chatter. In the forests, may the deer and wild goats multiply. In the orchard, may there be honey and wine.” And Ninshubur blessed the union of Inanna and Dumuzi. Inanna and Dumuzi made love again and again. Inanna says her fair Dumuzi did so 50 times, until his sweet love was sated.

Now Dumuzi says to Inanna, “Set me free Inanna. Come my beloved sister, I would go to the palace. Set me free. It is time for me to take my place on the throne that you have given me.” Inanna spoke, “Oh, my bearer of fruit in the apple orchard. Your allure was sweet.” And Dumuziu left to take his place on the royal throne of Sumer.

That’s where we’ll stop for today. I want to say a few things about this particular hymn or chapter in Inann’s mythology. I love the, I love the whole thing, the hesitancy and excitement, the whole dance that the two of them do, especially all of Inaanna’s preparations, and the various pledges that they make each other. It has a very contemporary feel, don’t you think? And it has the effect of dissolving time, and reminding us that although our way of life has changed a great deal, there’s a constancy to our psychology, to the human experience. For every young person who falls in love, who embarks on the sexual adventure of their life and finds themselves in that experience, there’s something beautiful and exciting and scary and poetic. It’s a timeless thing, which is one of the reasons that our myths, which attempt to the best that they’re able, through our metaphors and our symbols, to describe these universal experiences, retain their value for us.

Now, it is true that changes in our outer conditions are significant. For one thing, they bring with them a change of ideas. And there are a couple of things that I’m sure you noted about this hymn that I want to note, the first being the joyful sense of sacredness in this union, that their sexual coming together is profound in and of itself. And that it also reflects the fertility that is the creative potential in the world, and how important that is. We have these two, Inanna and Dumuzi, both of them partaking of the heavenly, that is the spiritual, that is the eternal dimensions, coming together. And so, in the image of their coupling we are told that the creativity around us is in fact, the nature of the cosmos, and that everything it produces, every thing that it produces, that we experience on this material plane, is touched by the divine. Is in some way, sacred in and of itself.

I also want to note that their fertility, that’s necessary to all of this and that is the heart of the metaphor, belongs to both of them. Maybe you noticed that too. Here we have a mythology that shows the necessity for fertility and strength and dynamism and vitality on both sides. How that yin and yang, to use those terms from the Tao again, are equally vigorous and possessing, in their own ways, the same qualities. Now, the idea that the divine, “god,” sacredness, is immanent, that is, found through the world, is clearly not original with me. There are many people who are talking about it and have been talking about it for quite a while. And those people who are living in indigenous cultures still today, are in possession of this awareness by and large. But in addition to its ubiquity, I often encounter a certain feeling of futility in modern people living in cultures like the United States, where I am. How do we regain that awareness of immanence? You know, now that we no longer trade in the myths of the male consorts of the great goddess, a figure like the shepherd Dumuzi, the great bull.

So, as part of our shared meditation on the challenge of how we might explore or re-enter into a sacred world, I’d like to read the opening pages from a really wonderful book, titled Lab Girl by Hope Jahren. This book won a National Book Critics Circle Award. I read it this summer, and it’s a memoir by geobiologist Hope Jahren about why she spends her life studying trees, flowers, seeds, and soil. Here is the prologue. Maybe it will give you some ideas about openings into this process for yourself, and if it encourages you to read the book too, great, all the better. She writes,

“People love the ocean. People are always asking me why I don’t study the ocean, because after all, I live in Hawaii. I tell them that it’s because the ocean is a lonely, empty place. There is six hundred times more life on land than there is in the ocean, and this fact mostly comes down to plants. The average ocean plant is one cell that lives for about twenty days. The average land plant is a two-ton tree that lives for more than one hundred years. The mass ratio of plants to animals in the ocean is close to four, while the ratio on land is closer to a thousand. Plant numbers are staggering: there are eighty billion trees just within the protected forests of the western United States. The ratio of trees to people in America is well over two hundred. As a rule, people live among plants but they don’t really see them. Since I’ve discovered these numbers, I can see little else.”

So humor me for a minute and look out your window.”

“What did you see? You probably saw things that people make. These include other people, cars, buildings and sidewalks. After just a few years of design, engineering, mining, forging, digging welding, bricklaying, window-framing, spackling plumbing, wiring, and painting, people can make a hundred-story skyscraper capable of casting a thousand-foot shadow. It’s really impressive.”

“Now look again.”

“Did you see something green? If you did, you saw one of the few things left in the world that people cannot make. What you saw was invented more than four hundred million years ago near the equator. Perhaps you were lucky enough to see a tree. That tree was designed about three hundred million years ago. The mining of the atmosphere, the cell-laying, the wax-spackling, plumbing, and pigmentation took a few months at most, giving rise to nothing more or less perfect than a leaf. There are about as many leaves on one tree as there are hairs on your head. It’s really impressive.”

“Now focus your gaze on just one leaf.”

“People don’t know how to make a leaf, but they know how to destroy one. In the last ten years, we’ve cut down more than fifty billion trees. One-third of the Earth’s land used to be covered in forest. Every ten years, we cut down about 1% of this total forest, never to be regrown. That represents a land area about the size of France. One France after another, for decades, has been wiped from the globe. That’s more than one trillion leaves that are ripped from their source of nourishment every single day. And it seems like nobody cares. But we should care. We should care for the same basic reason that we are always bound to care: because someone died who didn’t have to.”

“Someone died?”

“Maybe I can convince you. I look at an awful lot of leaves. I look at them and I ask questions. I start by looking at the color: exactly what shade of green? Top different from the bottom? Center different from the edges? And what about the edges? Smooth? Toothed? How hydrated is the leaf? Limp? Wrinkled? Flush? What is the angle between the leaf and the stem? How big is the leaf? Bigger than my hand? Smaller than my fingernail? Edible? Toxic? How much sun does it get? How often does the rain hit it? Sick? Healthy? Important? Irrelevant? Alive? Why?”

“Now you ask a question about your leaf.”

“Guess what? You are now a scientist. People will tell you that you have to know math to be a scientist, or physics or chemistry. They’re wrong. That’s like saying you have to know how to knit to be a housewife, or that you have to know Latin to study the Bible. Sure, it helps, but there will be time for that. What comes first is a question, and you’re already there. It’s not nearly as involved as people make it out to be.”

“So let me tell you some stories, one scientist to another.”

That’s the prologue to Lab Girl by Hope Jahren, and that spelled j a h r e n. Let me tell you some stories. One scientist to another. Well, and let me tell you some stories, right? One myth maker to another.

That’s it for me, Catherine Svehla and Myth Matters for this week. I’d like to welcome the new subscribers. I’d like to thank you for your ongoing support of this podcast, for sharing it with your friends and family, posting comments about it on Facebook, and positive reviews on other platforms. A special shout out to my patrons and supporters on bandcamp for their monthly financial contributions to the podcast. If you’re finding value in Myth Matters, I hope you’ll consider joining them.If a monthly contribution is out of reach for you right now, you can make a one- time tip in the tip jar at my website www.mythicmojo.com.

Feel free to contact me if you have questions or comments about today’s program. Please take care of yourself as we cruise into the final days of 2020. And until next time, happy mythmaking and keep the mystery in your life.