Click here to listen to Once Upon a Time and the Crisis of “Nothing But” in the season 2 archives on buzzsprout

“Everything is banal, everything is ‘nothing but;’ and that is the reason that people are neurotic. They are simply sick of the whole thing, sick of that banal life, and therefore they want sensation. They even want a war; they all want war…” –C. G. Jung from “The Symbolic Life,” CW 18.

According to Jung, most Western individuals suffer from a pervasive soul sickness, a sickness created by the one-sided nature of Western consciousness. The single-minded pursuit of “reason” has driven the deep need for wonder, meaning, and mystery into the unconscious and given rise to a dangerous literalism, and a world in which the lines between fact and fiction, truth and lie, are collapsing.

The one-sidedness begins with the mistaken notion that one makes a choice between two opposing options. Both impulses will direct your life as this is beyond your control, and the choice is not “between” reason and imagination, the rational and irrational, fact and fantasy.

The choice is to become more conscious of all of it, to learn to live with nuance and ambiguity, and live the mystery in you, that is you.

This choice is available to any person of intelligence and heart, who hears the invitation in “once upon a time” and begin a conscious quest for the symbolic life.

Transcript of Once Upon a Time and the Crisis of “Nothing But”

Hello, and welcome to Myth Matters, storytelling and conversation about mythology and why myth matters to your life today. I’m your host and personal mythologist Dr. Catherine Svehla. Wherever you may be in this wide, beautiful, crazy world of ours, you are part of this story circle.

“Once upon a time,” or maybe the story begins, “There once was.” Those are the classic openings to Western fairy tales, and there are similar devices that signal the beginning of tales like our fairy tales in other cultures. I want to begin by saying a word about the purpose of those words, “Once upon a time,” and what I see as a crisis, the crisis of “nothing but.” And it really is nothing less than a crisis.

So these words, “Once upon a time,” are signal, aren’t they? They signal to us that we are about to hear a particular type of story, a story in which unusual things are probably going to happen. Things that we may not experience in our typical every day existence. The words “once upon a time” tell us that we’re about to hear something that may or may not, in fact, probably mostly not, have happened in exactly the way that it’s going to be told. And so, in a sense is not true, not 100% factual and yet, is true because it contains metaphoric truth. Because, in fact, the story is about something that can only be conveyed in words from one person to another, with the aid of image, symbol, and metaphor.

We know this when we hear those words. We know that it’s going to be different from an account that we might read in the newspaper. And those words then, “Once upon a time,” are an invitation to the imagination, to lead us into the perspective on the symbols and the metaphors that’s necessary to understand the story, right?

Now, I said the crisis of “nothing but.” I juxtaposed those two things. And in that phrase, the crisis of “nothing but,” I am borrowing from an essay that C.G. Jung wrote in the “Symbolic Life” in Collected Works Vol.18. Let me read you these words from Jung:

“Now,” he writes,” we have no symbolic life, and we are all badly in need of the symbolic life. Only the symbolic life can express the need of the soul, the daily need of the soul, mind you, and because people have no such thing, they can never step out of this mill– this awful, grinding, banal life, in which they are ‘nothing but.’ […] Everything is banal, everything is ‘nothing but;’ and that is the reason why people are neurotic. They’re simply sick of the whole thing, sick of that banal life, and therefore they want sensation. They even want a war; they all want a war. They are all glad when there is a war: they say, ‘Thank heavens, now something is going to happen– something bigger than ourselves!”

C. G. Jung, “The Symbolic Life,” C.W. Vol18

That’s from the “Symbolic Life” by C.G. Jung and he was writing about the World War, and I’m going to make a leap of faith here and imagine that you hear, in Jung’s words, a very good description of what is going on now in the United States and many other parts of the world, which is that people are so desperate for something that we don’t have in our dumbed down, numbed down life of blind consumption, that we will buy up and turn to any form of excitement, no matter how sensational, or grotesque. And yes, I am talking about what’s going on in our political arena.

More and more often, I have conversations with friends who look at the folks on the “other side,” that is the side that support the president, the side that think that we’ll make America great again if we follow his program. The “other people” on the “other side” who somehow think that the Democrats are wrapped up in some pedophile ring or something. I mean, it’s absurd, right? It’s absurd. And in those conversations we use the words “absurd,” “unbelievable,” “stupid,” and “irrational.” But we’re missing something important. What we’re missing is this crisis of “nothing but” and this is a crisis my friend, that includes all of us. You see, the West, for a very long time, has been devoted to a fantasy of reason; a fantasy of reason, a fantasy of objectivity, a belief that the human being can be objective, can operate purely from reason. That there is only a literal truth, that we can know what is a fact, and that our histories are factual and objective truths, and not the myths of the victorious.

Now, the end result of all of this, and this is one of the great insights of depth psychology and C.G. Jung in particular, is that it has created a one-sidedness in consciousness. It has led to the denigration and repression and ultimate denial of our need for the symbolic life, that is our need for meaning and the experience of what we’re in, what I call the “mystery” on this program, that is bigger, that is “more than,” that addresses our deep need for wonder, our deep need for a sense of connection to the larger reality and to our ancestors, to the history of our species. Our deep need for the lived experience of the mystery and a sense of where that mystery resides, in our own being, and in our own lives. And this is what myth tells us, describes and connects us to– myth in its various forms, which includes everything that we now call the arts and poetry in particular.

If we don’t have this, you see, if we live in a one-sided consciousness, then all of these things that we need, all of these values, they will go into the unconscious and that’s what they’ve done. So now, they surface in these incredible ways that we don’t see. And because we have a habit of literalizing, which is the corollary to this fantasy of reason, they are degraded, they become an unquenchable thirst for the sensational. And they evince themselves in gullibility, and they push us towards a blind belief, and a faith in things that simply can’t be tested.

This fantasy of reason has been, in part, motivated by an important desire to separate human life and human societies in particular, from various forms of superstition, for lack of a better term. But in that quest, the distinction between the literal and the metaphorical has been largely lost. In an ongoing effort to make life more understandable, and so more controllable, many Western thinkers have attempted to make it simple. And, unfortunately, that’s just not the way life is. And life is not a matter of “either/or,” it’s a matter of “both/and.” This gets us back into the realm of myth, into a place where something can be true and not true at the same time.

Very deep and important needs and values can become distorted and grotesque and destructive, if the wrong means are used to fulfill them. It’s like an addict, an addict who is looking for release, for transcendence, for escape from the personality, all of these very important, necessary drives, by drinking or drugs, by entering into the temporary illusion that these substances can provide that when in fact, they numb and dumb and enslave and no matter how much of it you ingest, you will never, ever eradicate the underlying hunger.

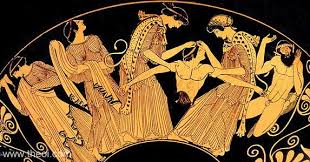

This reminds me of a play by Euripides, one of my, my favorite probably, of the ancient Greek playwrights, his play “The Bacchae,” which is about a city, Thebes, and a king, Pentheus, who resists the divinity of Dionysus. The god Dionysus is the god of the irrational and ecstatic release. And what ends up happening in this play, is that Dionysus displays his power and takes a kind of revenge on the city and on this king in particular, by possessing the women. Pentheus is torn into pieces by his own mother, who under the influence of Dionysus, imagines him to be a mountain lion. Now in writing this play for the Greeks, as a commentary on the experiment of Athenian democracy and reason, Eurpidies was not championing this kind of destruction. He wasn’t pointing at Dionysus and saying, “Oh well, we should go this direction instead.” The play was not meant to posit an “either/or,” it was meant to point out the pitfalls of an “either/or,” and in particular the pitfalls of a culture that thought that it could choose reason and thereby dismiss the irrational.

Euripides understood what Jung was writing about, that a one-sided consciousness in an individual or in a culture, is vulnerable to those powerful forces that have been driven into the unconscious. Jung often said that those who will not face something in their lives consciously will be forced to live it unconsciously, and experience it as fate. In that longer quote that I shared with you at the beginning of this podcast, he said people become neurotic because they see themselves and their lives as “nothing but,” because they perform this reductionism that is the result of reason. And that’s a less poetic way, the word “neurotic,” to talk about this experience of living it out as fate.

These themes can be seen in many of our fairy tales, and I found myself thinking in particular, of fairy tale called “The Queen Bee,” which was collected by the Brothers Grimm. I told this story in a podcast sometime last year, I think it was–the upshot of the story is that there were two sons of a king who left home to go and seek adventures, and they fell into a very wild way of living, and they just, they kind of fell apart. And eventually, their youngest brother, whom they never really thought much of, goes out and looks for them, and he finds them and the three of them begin traveling together.

At one point, they come across an anthill and the two elder brothers pick up sticks because they’re going to stir up the anthill and terrorize the little ants. But their youngest brother, whose name is Witling, says “No leave them alone, I won’t suffer them to be disturbed.” And so, they leave the ants alone. And the three of them travel on a little bit further, until they come to a pond where there are some ducks swimming, and the two eldest brothers want to catch a couple of them and kill them and eat them. And again, Witling intercedes and says, “No, I don’t want you to do that. I don’t want them to be killed.” And so, they leave them alone. And they go on a little bit further and they come to a bees nest. Now the two elder brothers want to smoke out the bees and steal the honey, and Witling intercedes on behalf of the bees, and again, they leave them alone. But the two older brothers are really grumbling and unhappy with all of this.

Eventually, the three of them end up in this magical castle, where they have the opportunity to bring the whole castle (which has been totally turned to stone) back to life. And of course, the reward is to marry a most beautiful princess. And as you may well have already guessed, it is Wilting, the younger brother who seemed weak and soft and dreamy and out of touch with reality, who ends up accomplishing this task, and he does so with the assistance of the animals that he has helped along the way– the ants, the ducks, and ultimately, the queen bee of the hive that he saved.

Now, if we’re going to attribute a moral or central lesson to this fairy tale, it would seem to be that kindness is rewarded. Witling is kind. He doesn’t indiscriminately kill the ants, or the ducks, or the bees, simply because he can. And so, then they help him. And yet, it’s really more than that, isn’t it? Because that kindness comes from a willingness to imagine that they aren’t “only” ants, they’re not “just” ducks, that there’s more going on than a group of bees in a hive and honey. Witling doesn’t live in the world of “nothing but.” Witling lives in the world of “both/and.” He lives in a world where yes, there are ants and ducks and bees and yet, they may be something more. And in fact, his willingness may mean that he has lived experience of them being something more, that he knows there’s something more to it, that he knows that he’s part of something that’s bigger than it might appear to his two older brothers.

In that particular podcast, we talked about this “something more” as being a sense of reciprocity. That a human being is one intelligence in an intelligent world, and that just as we are aware of the others, they are also aware of us.

This reductionism that we are conditioned into is dangerous, and it’s also a really limited and crummy way to live. You see, our choice is not between being a reasonable person who thinks and pays attention to science and looks for the facts, and being somebody who’s off in the ether somewhere, unreasonable, irrational, blindly believing in things. Paradoxically, if you insist too much on the former, you may well unwittingly become the latter.

The choice is to become more conscious, period. To become more conscious, which means becoming more conscious of the perspective that you are adopting, of the hungers that are driving your quest, whether it be a quest for meaning, beauty, or truth, that you understand the difference between the literal and the metaphorical and that you are able to move smoothly from one mode of thinking to another.

This is what we’re doing together here on this podcast, Myth Matters, and this is the meaning of that phrase I share with you every single time: “keep the mystery in your life alive.” This one-sidedness that I’ve been talking about, the crisis of the “nothing but,” can be solved the moment that we accept the invitation in those words, “Once upon a time.” Every time that you make an imaginative turn towards your life, knowing that that’s what you’re doing, you are building access to your own symbolic life. You are deconstructing the limited view of yourself and the meaning of your existence that has been the primary message of Western culture.

This is a task that will transform your life. And it is also the core transformation that’s necessary in the world today. As James Hillman said, it is our literalism that is the enemy. It is our literalizing, that is the disease. And my friend, it is our literalizing that may kill us. A heavy message, I know, a heavy message for heavy times. And yet, nothing is lost. The solution is here. You have intelligence, you have heart, and you have imagination, that is soul, and you have an inborn need for the symbolic life.

I’m putting together a new offering, I’ll be hosting it on my new teachable platform, that’s going to be a couple weeks of a self-guided practice through some of the things that we’re talking about. I realize that it may sound kind of abstract, but the reality of it is, it’s fairly simple in practice, once you have a little bit of experience with it. That offering is going to be called “Step Into the Fairy Glen.” If you’re on my email list, you’ll get an email announcement about it, and if you’re not on my email list, please listen to the next podcast or check in at mythicmojo.com. if that sounds like it might be interesting to you.

I want to give a big warm welcome to all of the new subscribers and a big thank you to my patrons on Patreon and supporters in the Bandcamp community. If you are finding value in Myth Matters then I hope that you’ll consider joining them and making a modest monthly pledge of support to the Myth Matters podcast. Those dollars really do make a huge difference for me right now.

I welcome your comments and questions about this podcast. I’d love to hear what you think about it. I’d love to know what questions it raises for you. This is a time of chaos and confusion. It’s also a time of tremendous possibility, and together we will find a way through. Before I leave you today I want to share a poem by Eleanor Lerman called “The Mystery of Meteors.” It’s one that I’m turning to often in these days.

The Mystery of Meteors

I am out before dawn, marching a small dog through a meager park

Boulevards angle away, newspapers fly around like blind white birds

Two days in a row I have not seen the meteors

though the radio news says they are overhead

Leonid’s brimstones are barred by clouds; I cannot read

the signs in heaven, I cannot see night rendered into fire

And yet I do believe a net of glitter is above me

You would not think I still knew these things:

I get on the train, I buy the food, I sweep, discuss,

consider gloves or boots, and in the summer,

open windows, find beads to string with pearls

You would not think that I had survived

anything but the life you see me living now

In the darkness, the dog stops and sniffs the air

She has been alone, she has known danger,

and so now she watches for it always

and I agree, with the conviction of my mistakes.

But in the second part of my life, slowly, slowly,

I begin to counsel bravery. Slowly, slowly,

I begin to feel the planets turning, and I am turning

toward the crackling shower of their sparks

These are the mysteries I could not approach when I was younger:

the boulevards, the meteors, the deep desires that split the sky

Walking down the paths of the cold park

I remember myself, the one who can wait out anything

So I caution the dog to go silently, to bear with me

the burden of knowing what spins on and on above our heads

For this is our reward:Come Armageddon, come fire or flood,

come love, not love, millennia of portents–

there is a future in which the dog and I are laughing

Born into it, the mystery, I know we will be saved

And that’s it for me, Catherine Svehla and Myth Matters. Thank you so much for listening. Take good care of yourself. And until next time, happy mythmaking and keep the mystery in your life alive.